Overdue

Academic institutions must change their approach to libraries and librarians

When I was a graduate student in English literature at Yale University, my roommate, a doctoral candidate in biology, noticed stacks of library books surrounding my cluttered desk. He remarked that he had never used the library. Instead, he used his computer to download PDFs of research materials. The fact that each electronically accessed file represented a direct use of library resources, made available through the work of academic librarians, completely escaped him. He viewed the library as a physical place, not a resource—and the library staff as having little to do with the materials on which he relied.

Twenty years later, this has become a pervasive viewpoint in higher education. Academic libraries are struggling to adequately provide both traditional library materials and services and information technology. Furthermore, with the shift toward internet-based resources, academic librarians spend significantly less time working face-to-face with patrons to help them find books or to explain how to use resources in the physical library. Instead, much of their time is taken up working behind the scenes to provide students, faculty, and staff with sufficient access to online materials and information. As a result of not seeing the professional library staff, many patrons no longer develop relationships with librarians—and others seem to have forgotten that librarians still exist. Decreasing financial resources, rising costs, staff shortages, and differing opinions about institutional funding priorities further complicate the situation. Combined, all these factors have fundamentally altered both the day-to-day lives of academic librarians and their place within the university ecosystem.

Although both libraries and librarians have gone through major transitions before—particularly with the advent of modern printing in the fifteenth century—the current crisis presents an unprecedented challenge to the ongoing well-being of both the institution and its staff and, by extension, higher education itself. As academic librarians, we must meet the present moment with courage, innovation, and tenacity.

Despite their reduced visibility, academic librarians are still the heart of academic institutions. On its website, the American Library Association lists the different ways in which academic librarians strengthen the entire college or university community: faculty, students, and staff can consult with them about the resources needed to pursue scholarship; librarians select and acquire relevant up-to-date resources and data based on those consultations; and librarians research new learning technologies and then teach faculty and students how to integrate those tools into their intellectual pursuits. In short, librarians are indispensable to the academic endeavor.

Despite this, as colleges and universities try to manage funding shortfalls, academic librarians are gradually seeing their institutional status decline, their pay reduced, and in some cases their positions eliminated. Simultaneously, many institutions are paring down library budgets to a troubling degree.

In a September 2020 survey of US academic library deans and

directors, the educational research group Ithaka S+R found that 75

percent of academic libraries had experienced a budget cut with a

“notable” proportion facing cuts greater than 10 percent. The reductions

affected all aspects of library budgets, according to the study, which

noted that “62 percent made cuts to collections, 59 percent allocated

cuts to staffing, and 53 percent cut funds from operations.” While some

colleges and universities may have marginally increased budgets when

campuses reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall trend remains

toward budget cuts.

Across the country, staffing cuts and shortages have led to a corollary shortfall in institutional memory and the professional expertise necessary first to identify and acquire relevant resources and then to ensure access to those tools for the academic community. Unfortunately, it seems inevitable that this strategy will ultimately have a negative effect on academic output.

The current crisis presents an unprecedented challenge to the ongoing well-being of the institution and its staff and, by extension, higher education itself.

To address these challenges, library directors must embrace creative solutions and new approaches. Practical adjustments could make a big difference. These include prioritizing funding for core resources and services that directly align with an institution’s mission, promoting the use of freely available online open educational resources, negotiating more advantageous licensing agreements with vendors and publishers, and using data analytics to better understand usage patterns and preferences.

Library administrators can also increase their

institutions’ visibility and save time and money by forming mutually

beneficial alliances with other groups and programs on campus.

Partnerships with information technology services, writing centers,

career centers, academic departments, and centers for teaching

excellence can increase awareness of the library and librarians on

campus in general and among campus administrators in particular. Such

collaborations also help demonstrate how libraries support teaching,

learning, and intellectual inquiry.

Likewise, college and

university administrators can strengthen the entire academic community

by raising awareness of the value of academic librarianship and

highlighting its centrality to the pursuit of knowledge and learning.

They can promote collaborative strategic ventures that involve the

library. They can also strive to change the perception of librarians as

support staff and instead set an example by recognizing them as

information professionals who bring significant expertise to the entire

academic community.

Furthermore, campus leaders can facilitate their library’s participation in interinstitutional academic library consortiums. These associations use their assets and buying power to collectively improve access to resources for every researcher at every institution in the group. One example of this is the Ivy Plus Libraries Confederation, a group of thirteen academic libraries that grew out of a three-university partnership. The confederation provides quick access to collections for researchers across the member institutions.

Finally, academic librarians themselves can help

improve the situation by overcoming what University of Illinois at

Urbana–Champaign librarian Fobazi Ettarh calls “vocational awe.” In a

2018 essay, “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell

Ourselves,” Ettarh argues that librarians must stop viewing their work

as a sacred calling and measuring their professional success by how

passionate they are about the job. Instead, the fulfillment of core

responsibilities should be the benchmarks of success.

Librarians, Ettarh adds, need to think more clearly about how to advocate effectively for what they need. Unionizing is one way to do this. Although the notion of collective bargaining may seem foreign to some library staff members, there is power in being able to communicate clearly to administrators as a group about the resources needed to provide the services upon which faculty and students rely. Unionization could also boost salaries, improve working conditions, and increase job security. Organizing can also strengthen the position of library administrators in advocating effectively for library staff and resources.

These suggestions are not a panacea that will transform deeply entrenched perceptions about libraries or librarians overnight. But with time and persistent effort, libraries and the people who work in them can come to receive adequate support. As Ettarh writes, “Libraries are just buildings. It is the people who do the work. And we need to treat those people well.”

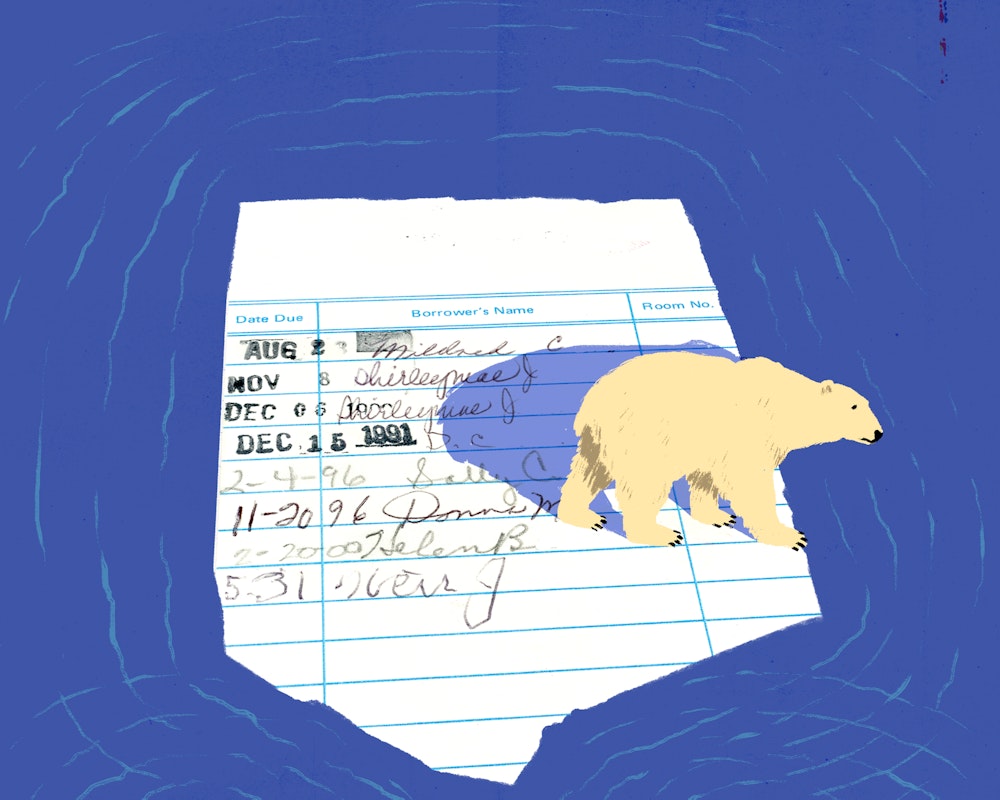

Illustration by Justin Renteria